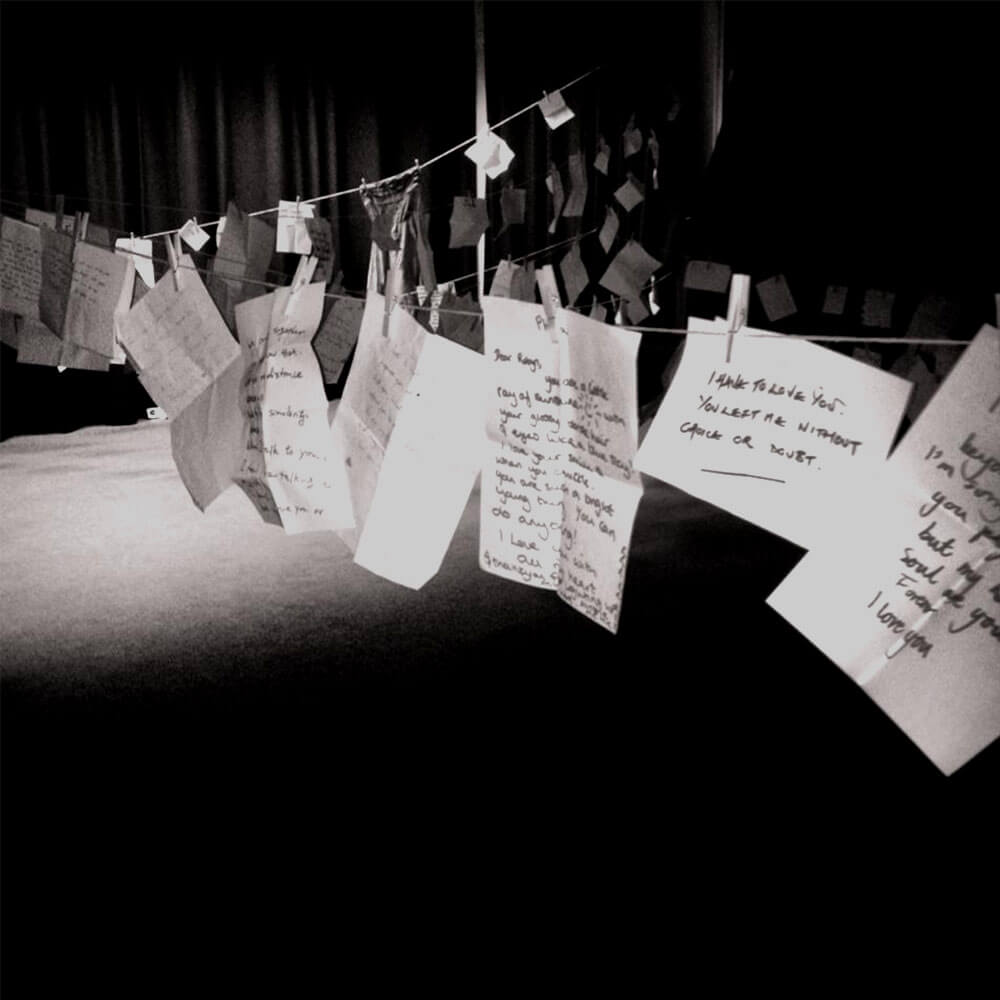

Love Letters

News

Before Texts and Tinder: The Art of Eighteenth-Century Love Letters

Thursday, 12 February, 2026BSU Senior Lecturer Dr Rachel Bynoth has studied the art of letter writing for many years. Now, with Valentine’s Day around the corner, another of our resident experts ponders the development of love and communication.

Today, in our quest to find love, we swipe right, we text and DM, we send emojis, GIFs and memes. Three seconds is all it takes to express interest—or indifference. But how did eighteenth-century individuals communicate their love? They composed letters.

In the eighteenth-century, finding a marriage partner was a torrid affair, for it was a decision on which the happiness of individuals, especially women, could depend. Letters were the emotional technology of their age, and love letters were carefully crafted to signal desire, restraint, interest and anxiety. For love letters were the space through which most courting couples decided whether they would marry each other or not.

Anxiety was a central part of the love language of eighteenth-century letters. One such suitor, George Canning Sr., wrote to his beloved Mary Anne Costello in 1767 that ‘My Heart panting with the most poignant anxiety for an event, whereon the happiness of my Life most absolutely depends, I take up the pen to explain my sentiments to the arbitress of my Fate, as clearly & precisely as that anxiety will permit.’

Even as George suggests that his letter is difficult to compose due to his overwhelming anxiety, George is performing a courting ritual. In this period, the heart was already associated with emotions, especially romantic feelings. The heart was also specifically connected to panting, meaning ‘to beat as the heart in sudden terror’ or ‘to have the breast heaving, as for want of breath’. By referring to his ‘panting’ heart, George communicated that his ‘poignant anxiety’ was due to the strength of his feelings of love, and likely his sexual feelings as well, implying that they were so overwhelming that he was almost unable to breathe. Yet even as he suggests he was struggling to write, his letter is well composed and neatly written.

Courting couples also communicated their anxiety of waiting for the post in their correspondences, as a signal of their affection. Whilst not unique to love letters, the strength of the anxiety was heightened. George wrote that ‘Five o’clock came, & brought no account in answer to my message…[w]hat horrid Phantoms assailed my Imagination! A Thousand terrors crouded [sic] on my mind. In vain did I call my reason to my assistance. What but the worst of ills could occasion her delay!’ George concluded that ‘I never knew how well I loved you till that moment’. Anxiety then was a powerful indicator of the discomfort felt until the next letter arrived, sending a hint to the recipient to reply as soon as possible to release them from the agony of waiting.

Yet love letters were not just written to communicate emotion; they were also written to prove one’s affection and commitment. In a later letter in 1803, Mary Anne wrote to her son that she and George Canning Sr. only lived around the corner from each other, but he had to prove himself worthy of her love. Their decision shows how love letters were both emotional performances and highly emotional objects, fraught with real anxieties about provision, sincerity, and self-worth. The love letter was the male’s claims of affection and devotion, attempting to get the female to formally accept his suit.

However, there was a delicate tension between sincerity and formula. Like with other letter forms, letter manuals provided examples of love letters, to teach the form and language of writing to one’s beloved. Yet it was a delicate balance as a love letter in that it had to come across as sincere and yet follow the broad frameworks of what a love letter should include. This is why it is such as art form, for it is easy to become formulaic, for which writers would be mocked for their perceived insincerity of feeling.

Above all, love letters were used to determine compatibility. Various topics including finances, work, interests and expectations. George was looking for a partner that could ‘repose my cares & anxieties’, suggesting that Mary Anne’s role as his wife was to take care of him and his needs. Mary Anne was looking for a financially secure match, with George writing to prove that he would become financially secure in the near future to provide for her.

However, despite the lyrical prose and sincere promises, love letters did not guarantee happiness. Mary Anne and George did marry but sadly he was unable to provide the financial security they needed. He died three years after they married, Mary Anne left destitute with two young children. Yet they remained in love through it all, showing how their love letters did reflect their mutual affection and shared interests. Mary Anne kept all of George’s love letters, and they can now be found in The British Library, over 250 years after they were first composed.

So, this Valentine’s Day, consider turning to the art of the letter to share your feelings. A keepsake that demonstrates your sincerity, commitment and affection to your partner.